Let’s for a moment accept all the clichés of what one generally assumes turn of the century Paris was like: tea at Maxims, ladies with parasols, Art Nouveau and the Moulin Rouge. And now imagine a Parisian concert hall in 1894, packed to the rafters for a premier of a new piece of music by that master of classical impressionism, Claude Debussy. The piece being performed is Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune. It is a beautiful symphonic poem which conjures an image of someone day-dreaming away a summer’s afternoon. It brings to mind the feeling of lying in a field listening to the birdcalls, listening to the sifting of moving air through summer leaves, the feeling of the heat of the sun on your face and the momentary desire to have your senses overthrown by nature.

Let’s for a moment accept all the clichés of what one generally assumes turn of the century Paris was like: tea at Maxims, ladies with parasols, Art Nouveau and the Moulin Rouge. And now imagine a Parisian concert hall in 1894, packed to the rafters for a premier of a new piece of music by that master of classical impressionism, Claude Debussy. The piece being performed is Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune. It is a beautiful symphonic poem which conjures an image of someone day-dreaming away a summer’s afternoon. It brings to mind the feeling of lying in a field listening to the birdcalls, listening to the sifting of moving air through summer leaves, the feeling of the heat of the sun on your face and the momentary desire to have your senses overthrown by nature.

The piece at the time of its premier was ridiculed, booed at, and dismissed as “darkly crazy, modern music.” You might not think that to hear it now, to the untrained ear it sounds just like any other piece of “classical” music, but this prelude arguably gives birth to the modern musical craft by embracing musical ambiguity and a whole host of combinations of chords, keys and harmonies. Brought together, these notes create lush, convoluted and colourful soundscapes, which transport music from the black and white into Technicolor.

The melting of musical clarity into a hazy intoxicating smoke that Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune represents, came only right at the start of this progression. Ultimately the tonal fences and walls, which had restrained musical experimentation in the past would crumble, leaving music unchecked and able to run free in a jungle of unnatural sound and hallucinatory sounds.

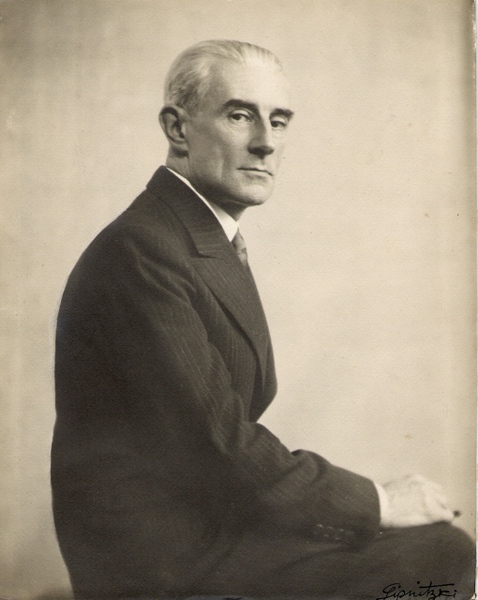

Maurice Ravel’s La Valse is another piece, composed a few years after Debussy’s work, that uses expressive music to paint a vivid picture. The form used is the waltz, which was, by 1920, the year of La Valse’s creation, unfashionable and outdated. Ravel grabs it by the scruff of the neck and breathes new life into it, before demolishing the old form waltz with a brashness that forges new and old together successfully. The music also represents the collapse of the old European order into the horrors of the First World War.

La Valse grumbles and bounces and sways to begin with, bringing to mind a dusty troupe of aged aristocrats, in a neglected ballroom. They are grouchy at first, but then they start to get into it. Society beauties regain their finesse, marquises and counts, regain their gentrified polish. Marie Walewska arrives, in a flourish of trumpets, walks over to the Duchess of Parma and slaps her across the face. She drops her champagne, the glass shatters on the floor and the attendees stop and turn and stare. Then the orchestra kicks in, all powdered wigs and livery, as the aristocracy rises and falls to the traditional waltz. But then the floor starts to shake, the walls crumble, debris fall to the floor and a chandelier whistles from ceiling to ground.

The doors burst open and in pile hundreds of soldiers, Cossacks, bombardiers and Prussian cavalrymen. As artillery pounds, the waltz struggles to be heard, but it fights on, the old order still dance, dresses and shirts blooded. As shrapnel flies into the engines, and the waltz whirls around erratically like the rotors of a downed helicopter, fighting against slashing strings. The bombs fall and the floor cracks and a great dark abyss can be seen, the waltz has one final bristle, one last gust, one last gasp for survival over the din of war and pillage, and then the whole affair tumbles into immortality.

heard, but it fights on, the old order still dance, dresses and shirts blooded. As shrapnel flies into the engines, and the waltz whirls around erratically like the rotors of a downed helicopter, fighting against slashing strings. The bombs fall and the floor cracks and a great dark abyss can be seen, the waltz has one final bristle, one last gust, one last gasp for survival over the din of war and pillage, and then the whole affair tumbles into immortality.