It is interesting, or perhaps it is not interesting, depending on your point of view, how random and unexpected themes can suddenly appear in our day-to-day lives, take root, flower, and die, all within the space of say, 48 hours. All you have to be is bored enough to spot them.

I would like to give you an example. When recently presented with a free day in New York, I decided to try the only mode of public transport that I have not diced with in the city before: the local bus.

Just like all European roads supposedly lead to Rome, all bus routes in New York appear to lead to the Port Authority Bus Terminal, a grey box that sits opposite the HQ of some local rag called the New York Times. To say it is dilapidated, decrepit, and most of all confusing, (the terminal, not the newspaper, although the description could be easily applied to both) would be a considerable understatement. Dimly lit corridors with flashing yellowing fluorescent lights lead to stuck escalators, petrol fumes poison lost pigeons, elderly people disappear down dingy rubbish-strewn stairwells never to be seen again, all while the engine sounds of moving buses echo around, yet remain frustratingly out of sight.

After a struggle I got the bus to New Jersey, chosen because I would need an inter-state ticket, which sounded romantic, but only required a 30-minute trip. The bus was dirty, but the seats were comfy and felt like an overused sofa in your grandma’s house. Opposite me sat a man in brown loafers reading a thick Sunday broadsheet newspaper, which he opened wide and rustled into the aisle with the page corners so close they almost tickled my elbow, an image I thought had left us along with Ronald Reagan and the walkie-talkie.

Hoboken was my chosen destination because it sounded remote and had birthed one of entertainment’s men of the twentieth century – Frank Sinatra. If you are interested, there is a small statue of him on the waterfront leaning jauntily on a lamppost. Old ladies seem to loiter opposite it and try to pick up guys.

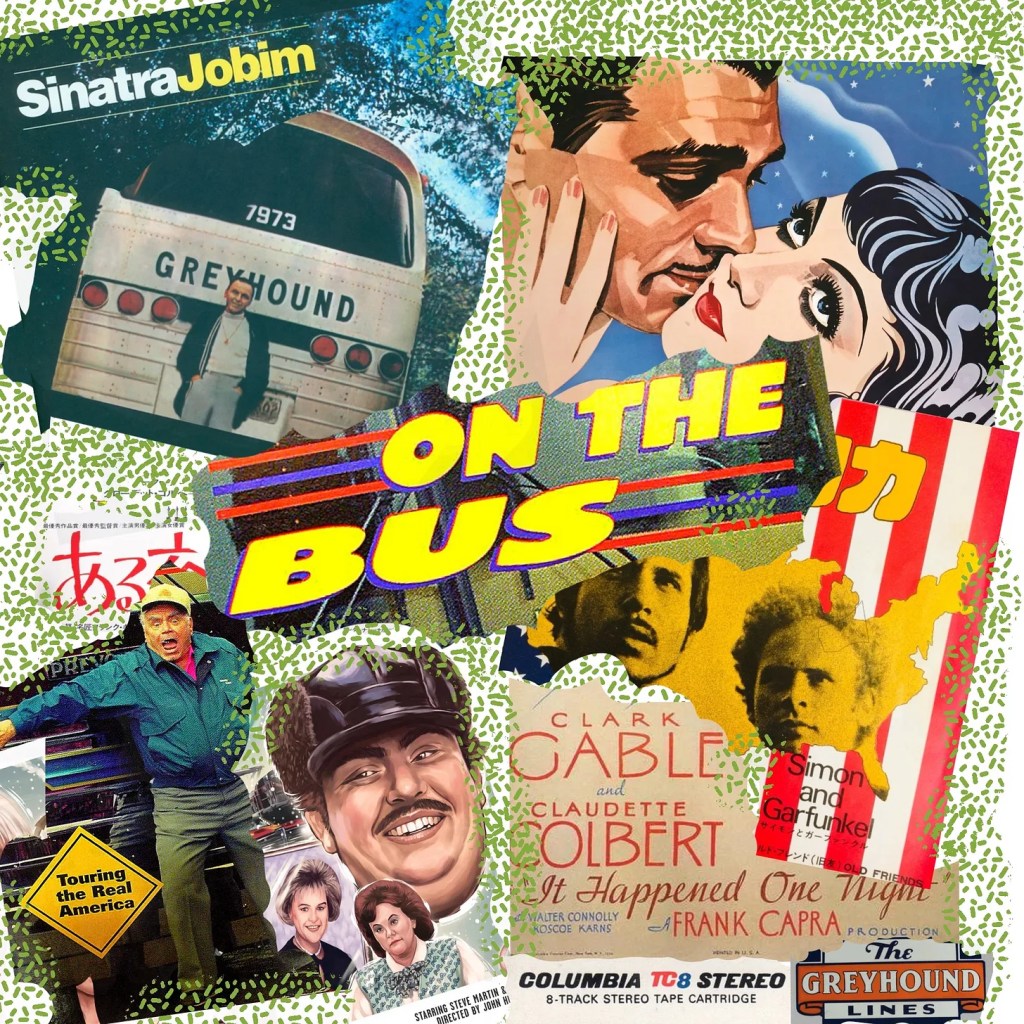

It was this vision of Sinatra twined with the bus ride fresh in my memory that really got the bus-theme up and running in my mind. Wasn’t there a rejected Sinatra album cover of him standing in front of a Greyhound bus, wearing a 60-style blue cardigan, white-t-shirt and gold medallion? You know, when he was trying to look cool for the hippie flowerchildren of 1968? And then, as I walked the lonely streets of Sunday-morning Hoboken, more dead celebrity bus-related factoids started to rain into my mind like asteroids from the Planet Stupid. Didn’t Ernest Borgnine (Ernie Borgnine, the guy with the Cheshire Cat grin who won an Oscar for playing a butcher in Marty), didn’t he get divorced and start driving around the US in a bus he called the SunBum? And didn’t they make a documentary about it called Ernie Borgnine on The Bus? Isn’t it on YouTube? Shouldn’t I re-watch it? And so it went on.

Anyways, a couple of days passed by, during which, regrettably, I had less time to think about such things, before the bus theme returned again. This time I was in my hotel room, I could see the top of the Empire State Building illuminated in the distance, and the television was on the blink. The channels were disappearing into a fog of static that seemed to have come from the same place as the guy on the bus with that broadsheet newspaper. Retro-town.

One of the only channels I could get was TCM. Fine by me. I love old movies. And what were they showing? Frank Capra’s It Happened One Night, with Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable – the ultimate bus movie. The gold standard. And it was just at the bit, that life-affirming wonderful bit, when everyone on that seemingly endless bus ride from Florida to New York, which makes the centre of the movie, start to sing:

The Man on The Flying Trapeze.

Whoa! He’d fly through the air with the greatest of ease

A daring young man on the flying trapeze

His movements were graceful, all girls he could please

And my love he’s stolen away.

Somewhere amid the verses an initially resistant Claudette gives in to the charms of Gable and they fall in love. Just like Steve Martin and John Candy fall in love in their own kind of way, during their own interminable journey across America in the hopes of making it home in time for Thanksgiving dinner in Planes, Trains and Automobiles. Why did that come into my mind? Because there’s a bus scene of course! Somewhere in the middle of the movie, Neal (Steve) and Del (John) go on a bus journey to St. Louis, and isn’t there a sing-song? Yes! Martin tries to lead the passengers in a rarefied version of Three Coins in a Fountain, but it falls flat, prompting everyman Candy to jump into a rambunctious version of The Flintstones theme.

Surely the singing on the bus scene in Planes, Trains and Automobiles was influenced by the singing on the bus scene in It Happened One Night? Surely? I have no idea. If you know the answer, send it to me on a postcard by ways of Stupid-ville, London. I’m really desperate to know.

So, after all these somewhat strange occurrences, on the flight back, when flicking through all the films I didn’t want to watch on the seatback television, what should I spot but a new documentary all about the life of Frank Capra, and it was full of talking heads, naturally talking about how wonderful the bus-singing scene was.

I looked from side-to-side and wondered if it was worth trying to get a sing-a-along going with my fellow passengers. The Wheels on the Bus perhaps? The Bus Driver’s Prayer? How about a song about Rosa Parks? Or Blakey and Stan Butler? Fearing I might get shot, I decided to stay quiet and ride the sky-bus all the way home with Claudette Colbert and Clark Gable.