Sometimes there are stories in newspapers of armchair archaeologists who spot hidden earthworks on Google Maps. They zoom in and see the outlines of long buried Viking longhouses or Saxon burial mounds or ditched flying saucers, and they head out with spades and buckets to dig them up.

Years later, the sparkly Saxon results of these digging sessions turn up in glass cases in the British Museum, while the spaceships are quietly hidden away, if they don’t take off moments after discovery and fly home with dirt and clumps of grass tumbling from their wings as they gain altitude.

I’ve never been an online archaeologist. My peregrinations through the towns and villages of Google Maps before holidays offer the perfect antidote to working for a living, but I’ve never found anything strange. Until recently, when I spotted the outline of a balloon cut out of grass in the middle of an industrial estate in my hometown of Oldham.

I briefly wondered if I’d discovered the compressed remains of a lost zeppelin, one of Stanley Spencer’s prototypes perhaps, the man who flew a rudimentary airship from Crystal Palace into central London in 1902, while throwing little muti-coloured rubber balls down from his basket high above the city to demonstrate what some nefarious force could do with bombs, if world affairs ever developed in that direction.

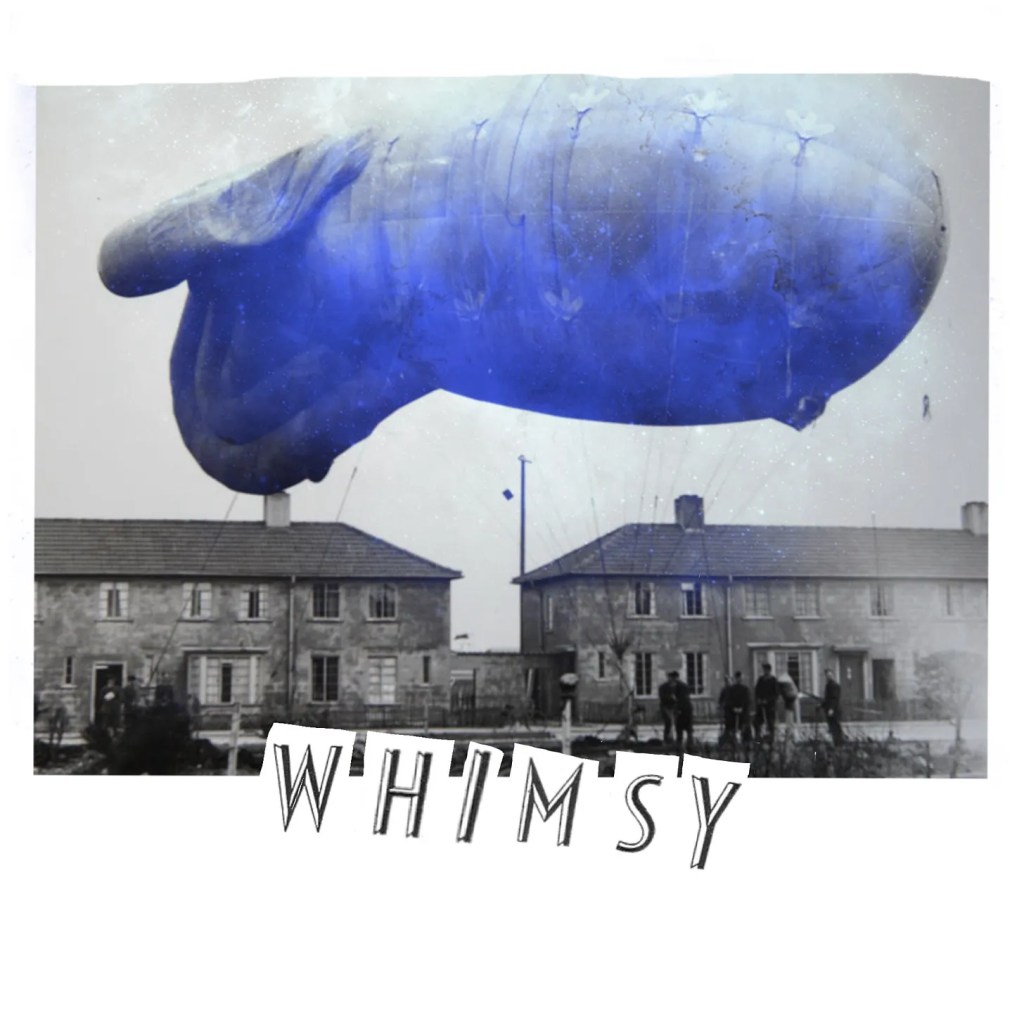

That was not what I had found though. The little grass airship was in fact a memorial to the Bowlee Barrage Balloon Centre, the Second World War-era headquarters of the 925, 926 and 931 Balloon Barrage Squadrons, which apparently stood next to the Jolly Butcher pub, in Middleton, near Oldham.

I’m not entirely sure of the purpose of a barrage balloon, but if you look at a picture of wartime London, or Manchester, you will probably see them hovering in the sky, silvery-grey spherical shapes, about as big as a helicopter but with tail fins and tethered to the buildings below.

They were there to deter low flying bombers and they were deployed in cities across the UK, nosing out from hangers and launched from airstrips like the one at Bowlee. Sometimes, they had netting strung between them to create a massive cartoonish net that could ensnare bombers like something out of Wacky Races, but the physics and the mechanics behind that you will have to look up for yourself.

War or no war though, there is something whimsical about balloons. Who doesn’t smile when they see one? With this in mind, I began a quick online trawl through the online newspaper archives to see if I could dig out any stories that painted a picture of the balloons’ whimsical nature rather their tactical contribution to the war effort.

The poetry dripped off the yellowing scanned newspaper pages almost from the moment I started looking.

One article from the early 40s in the Manchester Evening News described the balloons as “strange grey..silver creatures, like fish in the untroubled blue swimming above the coral reefs of dirty London chimney pots.”

Another story, in the Liverpool Echo, told the tale of an American soldier who while walking across Hyde Park, was “induced by a mysterious stranger” to part with £45 in return for a barrage balloon to take home as a souvenir. According to the Echo of Tuesday 8th of June 1943, when, an hour later, the gullible soldier returned to the Peter Pan statue in Kensington Gardens, where he had “expected to find the balloon deflated, packed up and ready to go”, he instead found the mysterious stranger had disappeared into the night.

“A barrage balloon,” the Liverpool Echo article goes on to say, “is not the sort of thing you can bring home and hang on the chandelier or put beside the aspidistra,” and on reading that I couldn’t help but think of the Biggest Aspidistra In The World in the song made famous by Gracie Fields, which grows so tall it has to be watered by the local fire brigade, “while its roots stuff up the drains, and grow along the country lanes.” An aspidistra with that kind of girth almost certainly would be able to host a barrage balloon on one of its humongous green leaves without much stress.

It is perhaps crucial to add in trying to bring some closure to this tale, that the article does note that the whole affair happened as the soldier was “returning from a party and whatever might have been his mood of the moment these occasions have been known to inspire elevated aspirations.” And the report goes on to paraphrase the Victorian historian, Thomas Caryle, who once wrote of French statesman going home from scandalous parties and “striking the stars with their sublime heads.”

Other reports from the time suggest the balloons often prompted a series of light-hearted cartoonish episodes that one imagines Walt Disney could have depicted in Bedknobs and Broomsticks. On Saturday the 16th of March 1940, for example, a headline in The Guardian yells “Men carried up by barrage balloon” and the article goes on to paint a picture of two members of the RAF being carried “over twenty feet into the air by a balloon” in an unnamed north east costal town after the tempestuous thing “got out of hand as it was being launched,” and caused the two men to be carried into the air on the mooring ropes. The rip cord was pulled, and the balloon was brought to the ground, but one can image them floating up into the clouds regardless, their shiny boots striking tottering chimney pots as they advanced higher and higher, off over the North Sea, before being deposited in a field of tulips in Holland.

The stories go on. In Greenwich, during a lightning storm, a barrage balloon dropped onto Woodland Terrace on a house occupied by a Mrs W. B Edwards. “The balloon deflated as it fell and struck the gable of the house bringing down the telephone wires and Mrs Edward’s washing line,” the story reads, while another balloon in Crystal Palace came down on a garden allotment and got caught in some apple trees.

The London Evening Standard of spring 1939, shows a picture of a crowd standing outside J. Salter’s, a dentist at No.178 Kilburn High Road. Everyone is looking upwards, and it must have been a windy day because the people in the photograph are all holding on to their hats.

Another picture shows what they are staring at, a barrage balloon being launched from the top of the Gaumont Cinema, with long multi-coloured shimmery streamers tied to its tail. These beautiful skyborne ornaments were flown above cinemas across Kilburn to advertise the George Formby film “It’s In The Air”, which came out in 1938, and is a gentle farce about a hapless rejected air raid warden who tries to join the RAF just before the war starts.

Those cinema topping balloons must have been quite mesmerizing dancing in the air as grey London geared up for the Blitz. A bit of whimsy to blow the cares and woes away, or as George Formby sings with his Gibson banjolele in the film:

Do I seem a little loony? Well, I am a little loony

For I’ve not been feeling myself all day.

Its… in… the… air … this funny feeling everywhere

That makes me sing without a care today

As I go on my way it’s in the air.

It’s… in… the… air… there’s great excitement here and there

The sun is shining everywhere and spring

Makes everybody sing, it’s in the air!