Prologue

George Washington-Plunkett died in a lighthouse on a Tuesday. He had never imagined himself dying on a Tuesday, it was non-descript, not like expiring on a Friday or a Sunday which had a little more apostolic value. Not that he ever saw himself in those terms of course, although other people had done, when he was younger. On finding the body in the second floor bedroom, on its side, facing the open curtains and a view of the bay, Mr Ryan, George’s personal assistant of seven years, set in train a string of events which had been long planned.

First he recited the Agnus Dei, in Latin, before crossing himself theatrically and concluding, “In days of old when knights were bold and toilets weren’t invented, men dropped their load upon the road and walked away contented.” Then, climbing the seventy four white stone steps to the lamp, he over-rode the delicate controls to flash the lighthouse bulb fifteen times. A Mrs Charleston-Charleston, Dowager Duchess of her own back yard, saw the signal and reacted by holding a solemn seven minutes silence in her outdoor coal shed.

Collecting fifty-seven wooden apple crates, which had been saved in the pantry for the last three years, Mr Ryan proceeded to fill them with ornaments, pictures, papers, records and letters, even cutlery and linens, for transportation to a bank vault in Lower Manhattan, where the money had been put in place to have the effects stored in perpetuity. Anything bigger, cabinets and bedsteads, were burned by the river. Attending to the grimmer part of his duties Ryan then dressed George in his only handmade suit, pinning a Vatican medal to his left lapel, before wrapping the body in a white bed sheet. He then called Mr Larry “lacking a looker” Lambert, a fisherman, so called because he lacked his left eye, who had been forewarned of the role he would play four years before the event occurred. Lambert was told not to ask any questions, only to assist Mr Ryan in the removal of the body to George’s wooden sailboat, The Rhona Lindesay, and to expect payment promptly.

Ryan then set sail, alone, with a bottle of brandy, due east and past the Elmsbury Archipelago’s daunting rock faces, passing close to where the green dragon, with its brown and red pointed tail fins dipped and dived, before arriving at a placid stretch of sea, known for its calm. Placing rocks in the sheet to weigh it down, Mr Ryan dropped the back of the boat and rolled George unceremoniously into the deep, standing to give a half-hearted salute as the body bubbled downwards. Neither had been military men, but some kind of mild gesture seemed suitable. Upping the throttle and making for home, blue surf beating off the wooden bow, Mr Ryan returned to the empty lighthouse, tossed the keys to the tiled floor and walked off into the rest of his life.

Biography

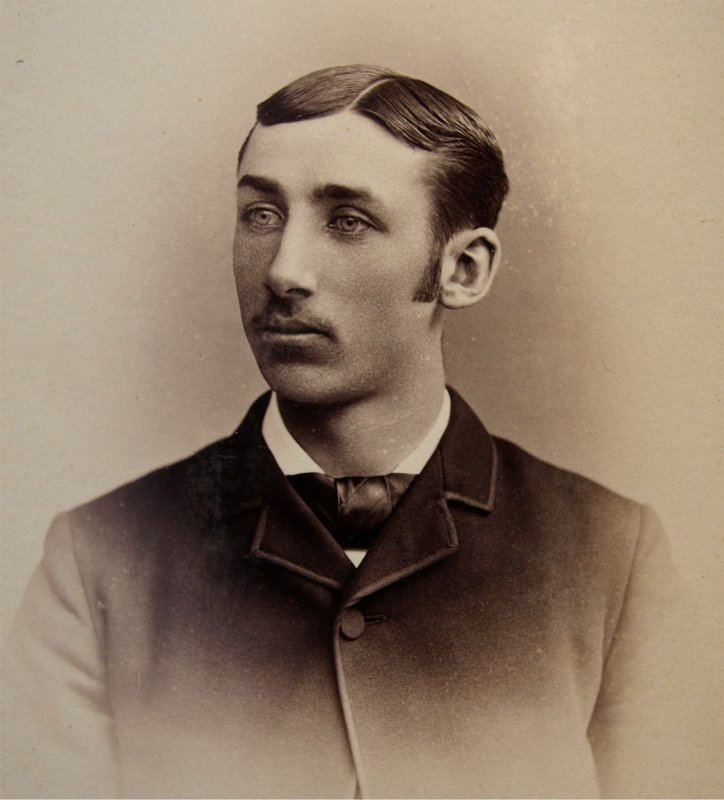

“The story of Plunkett is more American than America itself,” wrote Upton Sinclair in “I, Governor of California and How I Ended Poverty” in 1933, “Plunkett didn’t pull himself up by his bootstraps, rather his boots flew onto his feet at mystical command, tied themselves and marched him into a pile of dollar bills.” Born on the 5th of June 1879 to Charles Plunkett, Connecticut’s only deaf piano tuner and Mary Dalton Plunkett, an heiress to a lost battery chicken farm fortune, the first written mention of George Washington-Plunkett can be found in a letter from Mark Twain ( a neighbour) to William Dean Howells in 1886: “While idling away an afternoon by the river, near Hartford, I chanced upon a young boy of seven or eight, stood in the water, continuously catching fish, one after another he reeled in, as if the boy were magnetic and the fish made of tin metal, until the pile next to him stood nearly as tall as me.” Twain goes onto recall: “He told me his name was Georgie Plunkett, son of Charles the piano tuner, who had left my upright keyboard unplayable the previous Wednesday and got his britches tangled in the piano pedals.”

With the help of Twain’s locutions tongue the story of “Little Georgie Plunkett the Fish Catchin’ Boy” spread up and down the river, with Ma and Pa Plunkett being inundated with requests for George to make personal appearances at river-side county fairs and river pageants to display his miraculous skill. The story that George would distribute his weighty catch to elderly parishioners was a myth, he actually sold the fish to merchants at very high prices. Yet the tale lives on and in certain towns and villages along the river’s edge the 5th of June is still celebrated as “Georgie Plunkett Day” which sees local school children calling on elderly neighbours to deliver platters of fresh fish, before singing a rendition of “Smilin’ Georgie (Catch us a Salmon)” the poem Emily Dickinson wrote for George and posted to him on the back of a sodden beer mat.

After George’s parents were murdered by disgruntled trawler men in 1895 he was left alone in the world. His paltry inheritance of a set of tuning forks and several elderly battery chickens was, however, no set back, the money from the fish sales being more than enough to buy his way into Harvard University, where he shocked many by passing the entrance exams with record high marks, despite a total lack of formal education.

A written reference to George can be found in The Harvard Crimson newspaper in January 1898 which notes a “Mr Washington- Plunkett,” attending an end of year ball and attempting to set fire to the banqueting hall curtains. Of slightly more importance was the woman reported to be on his arm that evening, Mademoiselle Angelica de Mazarin, a French aristocrat, with royal blood, whose father was the incumbent French ambassador to the United States. The brief romantic match was an unlikely one, he was not terribly popular with women and students and collegiate staff alike were left wondering how a man one former girlfriend had labelled: “The most oily and insidious wretch you could ever have the misfortune to encounter,” had managed to win one of the renowned society beauties of the era.

Angelica’s diary entry for March 5th 1898 offers the most telling insight into their relationship: “George is a bastard. A charlatan of the highest nature. I have never heard him say a word in truth, only ever in jest and his language is something of which a sailor would be ashamed. His consistent practical jokes, like locking me out of the house and having me arrested for loitering before entangling himself in the washing mangle and playing dead, are tiresome. And he broke the mangle. His breath smells, his hair is left uncombed and his chin unshaven, when he drinks, he drinks too much and often becomes lairy after only a sip of ale. He talks only of pistols and baits cockerels in the bedroom. He is rude to my mother, he is rude to my father, he is rude to my grandfather and only last week he flicked a raisin at the Archduke of Austria and slapped a nun for standing too close to him in the line for Holy Communion. Nevertheless, I love him dearly.” Two months later she was committed to a state sanatorium where she remained until 1964.

Graduating Harvard, George, still flush with cash, opted to delay returning to Connecticut and instead travel to Europe to take in the continental sights. He visited London and Royal Ascot where a considerable wildcard bet on an un-favoured horse paid off handsomely, prompting the Prince of Wales to remark famously from the royal box: “This Plunkett is my man in any scrap,” before tripping over a footstool. Rome and Paris followed and in 1900 George caught world-wide attention becoming only the second man in history to break the bank, several times, at the Monte Carlo Casino. “He just kept going and going,” blackjack dealer Marcel Lindberg told the International Herald Tribune, “the cards always went in his direction, table after table, had the casino not closed, well, he would have gone on all night and no doubt won the Prince’s crown itself.”

Decamping to a seafront hotel in Nice, George was mobbed by a press hungry to join the points of his story together, the folklore from Connecticut, his performance at Harvard, the unlikely dalliance with Mademoiselle de Mazarin and his triumphs in London and Monaco. He was presented either as a man whom fortune appeared to consistently favour no matter what the circumstances, or as one of the century’s great cheaters.

In Rome, on hearing of the situation on the French coast, Pope Leo XIII believing that the story could be an example of holy or apostolic power being channelled through the life of a single individual, dispatched a team of Vatican observers to find George and report back to the throne of St Peter’s regarding what His Holiness termed as: “The possible presence of messianic qualities within Mr Washington-Plunkett.” The team would later return to describe George as: “Rather small, slobbery, covered in hair, playful, and pious in a roundabout sort of way,” in a sentence which has puzzled religious scholars for two generations.

It has since been assumed that the Vatican commission, most likely, only found George’s basset hound Marshal, and concluded the hunt at this juncture after one of their number contracted jaundice. Nevertheless the Pope appeared satisfied with the conclusions and began the process which would lead to George’s beatification, overruling numerous protestations and many ecclesiastical criteria. The procedure was quickly halted on the Pope’s death before it could be concluded, a development which Leo’s successor Pius X labelled: “The biggest strike of luck since the resurrection!” in his famed encyclical: “Dancing Girls, Beer and Cigarettes, Please!” from 1905.

Distinguished German scientist Otto von Steinhart, fascinated primarily by the Connecticut fish episode, offered his own thesis. In a paper entitled “Thoughts on the Events of 1900” perhaps better known as “Steinhart’s Tiny Bundles Theory” he wrote: “It is my belief, as I have noted in papers previous to this, that every human body is comprised of millions of tiny bundles of electricity, the same electricity that powers the Edison light bulb no less. The amount of electricity collected en masse is equitable in each human body and is just the right amount to sustain and power a balanced existence. In the case of Mr Washington-Plunkett the “tiny bundles” are supercharged and are producing twice the normal level of electricity, thus creating an un-natural aura around him which disrupts the very organised and balanced nature of our planet. Thus the fish swim towards him, some people feel overcome by him, and the sheer power of his overcharged mind forces the cards to fall in his direction. If one was to measure his temperature it would probably be found to be raised, if one was to stand next to him a gentle humming would be heard emitting from his person.” Thomas Edison would later dismiss “Steinhart’s Tiny Bundles Theory” as “typical German hogwash.” For the next ten years though George would be consistently pestered by people requesting permission to place an ear to his chest to hear the legendary electronic humming, a request he always denied, however numerous former girlfriends, doctors and clergymen recall hearing no such noise.

Spending the rest of the year on the Riviera playing the part of the bona fide American aristocrat, George became renowned for using his money, fame and unfathomable luck to full advantage. A story which circulated on the French coast for a while in the months after the Monte Carlo win and the publishing of the Steinhart theory, involved George attending a party at Geer DeWitt’s house, the heir to a great Rhodesian diamond fortune. Impoverished and looking to make influential friends the Prince and Princess of Monaco were also in attendance. After striking up a conversation with Her Serene Majesty and regaling her with tales of European daring-do, the Princess, possibly overcome by Steinhart’s super charged particles, or possibly overcome by white wine spritzer, lost control of herself and jumped on George in a dimly lit quadrangle, an altercation, which, naturally, drew to a conclusion in Greer DeWitt’s bedroom. Noticing the absence of his beloved wife the Prince began inconsolably searching the villa believing her to have been kidnapped by Prussian mercenaries, who he had a constant fear of after spending twelve hours trapped in a steam powered lift with several of them at the Great Exhibition.

On finding his wife in bed with George the Princess, it is claimed, sat up and screamed, “It wasn’t my fault Charlie, it was the frizzy bundles!”The Prince approached the bed and replied, “Is he humming? Well is he?” gesticulating wildly towards Plunkett’s chest. Pulling away from George in mock disgust the Princess shouted back, “Oh yes, yes, Charlie, he’s been making all sorts of awful noises!”At this point the Prince is said to have dived towards George while drawing his sword and yelling, ”Get your fucking particles out of my fucking wife, you Prussian bastard!” After politely explaining that he was American not Prussian, George jumped out of a window and shinned down a drainpipe.

Returning to the United States in 1908 he was met in New York harbour with an unexpected hero’s welcome, unexpected because nobody could think of a single reason why he deserved it. Nevertheless the newspapers whipped up a furore with one editorial from the New York Times reading: “Welcome home to our brave smiling boy, from Connecticut to La Belle France, the world falls at your feet!” Never one to miss out on a photo opportunity newly elected President William Howard Taft invited George to the White House, where he was pictured, with the Presidential arm around his shoulders, surrounded by the cabinet.

The President provoked audible gasps from the gathered political big-wigs when he mischievously, sincerely or in jest, historians remain divided, offered George the position of Vice President, on the condition that he brought his:“Trademark lucky boots to the Senate floor.” When the President was informed that no such footwear existed and that George’s lucky streak remained unexplained, the President rescinded the offer. “Another stroke of luck for Mr Washington-Plunkett!” declared the Washington Post.

An encounter later that evening at a State Department dinner held in his honour would prove pivotal. Finding himself sat next to Rhona Lindesay, the daughter of the Secretary of State, George fell head over heels in love. Saying later in a rare recorded interview unearthed by The George Washington-Plunkett Foundation: “She was everything, right there in front of me, everything, all that beauty and all that charm, I offered her a cigarette and she slapped me across the face.”

Their encounter went unrecorded, but in 1938 Orson Welles devoted an entire episode of “The Mercury Theatre on the Air” to telling the, highly dramatized, story of George’s early life in a radio play, with Joseph Cotton taking the role of Plunkett and Geraldine Fitzgerald the part of Rhona. No recording of the production survives, except for a paper script, which in inimitable Welles’s style sees the action moved to 1920 and the language take on something of a B movie quality. The final lines of the famed “State Department dinner scene” are verbatim however, and were given to Welles by Rhona herself, during a couple of New York lunch dates the pair shared in the run-up to the play going to air.

George: I’ve never been more in love with anyone in my entire life.

Rhona: We only met five minutes ago.

George: Five minutes ago, ten minutes, an hour, a day, a lifetime, what does it matter?

Rhona: God, who’s writing your lines, darling, American Greetings?

George: No, the gents who work on the motion pictures write for me, don’t you see, I’m John Barrymore and you’re….uhm…..Evelyn Brent.

Rhona: Oh no, no, no, you’re far too, far too, ungainly to be John Barrymore.

George: And you’re far too pretty to be Evelyn Brent.

Rhona: Now look, I’ve heard all about you, the fizzing particles, the glamorous women, rampaging through the South of France without a care in the world and, before you start, it all sounds so….boring.

George: Boring, and being the Secretary of State’s daughter is one long jubilee I suppose?

Rhona: I get perks, I get to stand here now and talk to the man of the hour, or whichever man of the hour happens to be passing through, last week it was Haile Selassie, the week before, Winston Churchill, we tend to honour men of substance, you see, men of weight, so why we’re serving dinner to the latest half-baked sensation to arrive from the continent I’m not quite sure.

George: Mistreating the guest of honour, now that is funny.

Rhona: This whole business is far too laughable to be anything else. So what happens in the next reel John Barrymore, where do your writers go from here?

Geroge: Well you seem to think it’s over, but I think it’s just beginning.

Rhona: Ha! Optimistic aren’t we! You know when I was a little younger I took ballet lessons, I learnt to cross my legs three times in mid-air, it’s called an entrechat, Nijinsky could do six, but he was a genius. Six entrechats that would be a beginning, or five, or even four and there’s no luck in that, darling, just pain and sweat.

The encounter with Rhona stayed with him, she was so unimpressed, so unaffected by whatever it was that was inside him, be it the electronic bundles of Steinhart’s anatomical sketchbooks, a sliver of the Holy Spirit, or just the bones and vessels gifted to everybody else, but in his case forming some kind of numeric and statistical one-off. Rhona Lindesay, in a brief conversation, opened George’s eyes to the benefits of a normal existence, free of the press and celebrity his unwarranted success had garnered and free of the mysterious or statistical glitch which robbed him of the need for hard work.

Rhona remained unmoved by his increasingly misguided and extravagant attempts to win her however and the press became more feverish with every stunt he pulled off. There was the life size cake, a mile long tapestry sewed by Peruvian seamstresses detailing the main events of her lifetime, the time he recruited the Fisk Jubilee Singers to perform “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” outside her house while Douglas Fairbanks and Lillian Gish danced the tarantella in her backyard, and, of course, there was his conquering of Mount Lindesay, in Queensland Australia, which he named in her honour and which still retains the name to this very day. Although she was moved by his charms and could see something in his personality, an admirable persistence, which she did admire, Rhona could never get past the notion that she was just some kind of final barrier to over-come, the last pin to fall and if she did give-in to him, then she would be quickly surpassed by whatever came up next on his radar.

Those around George during this period would claim that he was truly heart broken by Rhona’s reaction and became convinced that his failure in love was some kind of cosmic payback for the luck he had enjoyed for so long. In late 1913 he received a letter from Rhona explaining that: “Although I am touched by the attention and that any one person could be admired so much by another (undeserving as I am) I simply could not love a man whose lot in life was derived from chance, I would never want to be seen as another part of your God given windfall and all the celebrity that would garner.” The letter drove him over the edge and a frenzied attempt to break his lucky streak followed, a dramatic spiral of gambling dens and racetracks, with money being thrown at bookmakers only for bigger returns to appear in his pockets every single time, his fame never abated either, he was mobbed by crowds at Churchill Downs and was lucky to escape from the crush with his life.

Rushing into the Lenox Hill hospital in 1914, after a failed suicide bid during which he had thrown himself in front of a tram only for the driver to die of a heart attack and fall on the breaks before the carriage could hit him, a distraught George demanded doctors remove: “Whatever it is that is ruining my life.” Seeing their chance at potential fame physicians, physiologists and psychologists rushed to Lenox Hill from all across the world to offer their diagnosis and cure. One suggested that he had been born with metallic insides and prescribed a new chest, while another advised reading the complete works of Charles Dickens upside down for forty six years. One doctor, from France, brought a home-made suction system comprised of a short length of copper pipe and some bellows, which he claimed would expel the Steinhart particles from every orifice in the body, as well as any other odious gasses, or even feelings, which may be troubling him. “Even melancholy could be blown away with a sharp gust,” claimed the doctor. A Muslim imam recommended prayer, a Jewish rabbi recommended prayer and a Roman Catholic bishop recommended prayer and a healthy donation to church funds.

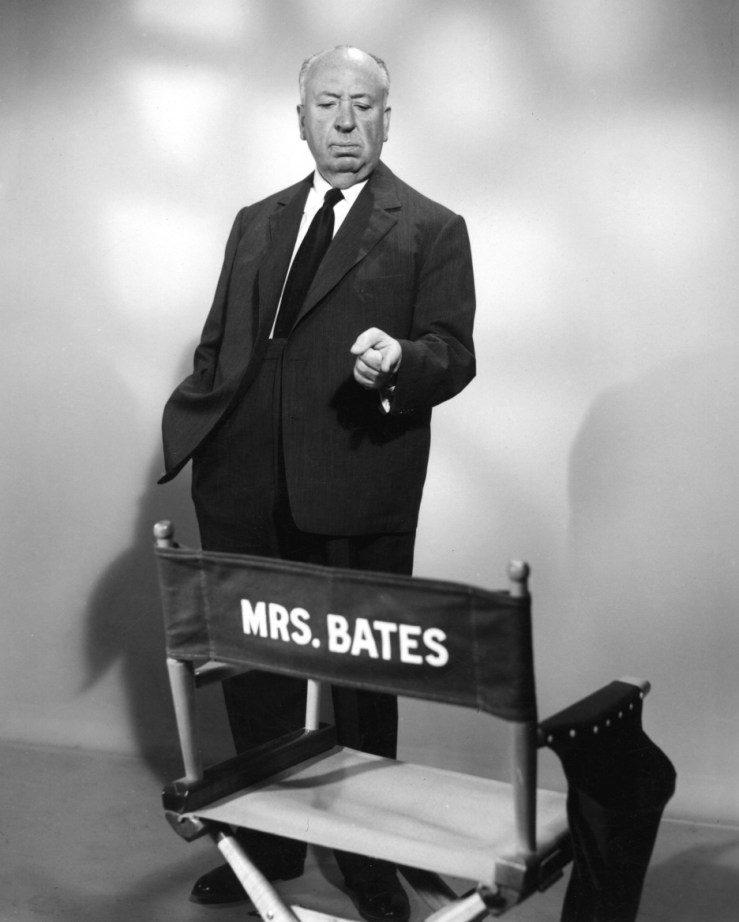

In a fit of rage, in the face of hundreds of answers, but no workable solutions and continued refusals from Rhona, George left the hospital, left New York and left the public scene. Buying a lighthouse under an assumed name on the Cape Cod coast, he hired a Mr Gregory Ryan as his personal assistant, bought a wooden skiff, which he named The Rhona Lindesay, and lived his life by the sea, painting and anonymously donating the pictures to local craft fairs. Every now and then a reporter would arrive at the door, thinking, after much trail chasing, that he had found the missing George Washington-Plunkett, always to be met by the loyal Mr Ryan, who dismissed them, insisting that this was the home of a Mr Edward Kent, a former piano tuner, turned lighthouse keeper.

George died in 1922, young at 43, an aging and discredited Steinhart would claim that this was caused by the now infamous “electronic bundles” speeding up his metabolism, prompting an early death. But Mr Ryan, commenting to his daughter on his deathbed in 1960, after a lifetime of silence, claimed he had found several empty pill bottles by George’s body. It was an admission Ryan always planned to make, in an attempt to prevent further posturing from Steinhart, but he took the memories of the boat journey with George’s body and the events which followed to his grave.

Giving the world the inside story on Plunkett’s final days based on the recollections of her father, Deborah Ryan, would conclude her bestselling book “Daddy and Georgie Plunkett” published in 1975, with an accidently ironic pointer to what was to come: “George Washington Plunkett is a caricature to many, an odd, mysterious and unexplained figure from a bygone age who seems unknowable to us here in the 1970s, but we will know him better, time is a first rate counsellor.”

Epilogue

Rhona Lindesay received the letter from a New York attorney on a Tuesday in 1922, and on meeting Mr Alphonse Agrippa and his assistant, all dyed hair, three piece suits and black mustachios, in a ramshackle lean-to just off Madison Avenue, was told of the existence of a Cuttyhunk Harbour Lighthouse, not far from Westend Ponds, in Cape Cod, Massachusetts. The building was to be awarded to her in trust for one month, a period during which she was asked to oversee the excavation of the lighthouse floor. The will of George Washington-Plunkett then decreed that the Cuttyhunk Lighthouse be given over to the care of a Mrs Charleston-Charleston, who would ensure the house was kept in its current form, in keeping with the surroundings. Anything discovered during the excavation would belong to Mrs Rhona Lindesay solely and should either be kept or given away to causes seen to be fitting, and in the repercussions of anything found, the name of Mr Washington-Plunkett should never be mentioned, the will stating in his own words: “A life-time of acclaim was quite enough, never mind an afterlife full of the same.”

Sailing from New York harbour to Boston, Rhona, two brothers, their children and several sets of cousins, armed with hammers and axes and plastic buckets and iron poles, travelled to Cuttyhunk. Rhona, widowed, had married a year after George’s disappearance, to a Wall Street millionaire, who had shot himself in the temples in 1920 after losing his fortune in an ill-advised wager on a game of pitch and putt. Photographed by her brother walking across the Cape Cod grass, headscarf rippling in the sea breeze, greying hair licking upwards from below its mustard silk, Rhona appears to cut a much more vulnerable figure than the woman who had so publicly refused Plunkett several years earlier. Writing in her diary she said in retrospect: “I have regretted that since, of course, love should be listened to, and George’s total disappearance from life has oddly convinced me of his sincerity, or perhaps, sincerity has been my gift to him.” Nevertheless, despite her marriage, she never forgot George, and George never forgot her. It was a bond based upon a devotion to what could have been and the lessons learned and it had seemingly strengthened in absence.

A note and twenty million dollars were found in a hidden vault beneath the lighthouse floor, a fortune for the time, the money raised from when George played his luck across Europe and the United States, little of it spent since those heady days of the early 1900s. The note puzzled everyone present, except one, and read simply: “Six entrechats, or as close as I could get.”

Rhona was resistant to begin with, showing some of her renowned fire, declaring after the discovery to a cousin twice removed: “How dare the lazy little bastard leave all this business to me!” She did as she was asked though, placing the money in an anonymous trust which dealt with financial matters beyond her knowledge and chose causes deserving of George’s money, although these were always passed onto her for final approval.

The trust attracted considerable attention and the public and the press often put the disappearance of George and the appearance of the trust years later together, but despite numerous attempts to infiltrate the organisation, no truths were ever found out. However, this did not prevent George’s childhood home in Connecticut, and after Mr Ryan’s death, the Cuttyhunk Lighthouse too, from becoming shrines, attracting all kinds of mystics, wanderers and free-spirited individuals, as well as those simply down on their luck and hoping to catch a break by breathing the same air as “Smilin’ Georgie.”

George’s true generosity was not revealed to the world until ten years after Rhona’s death in 1983, the trust, now renamed The George Washington-Plunkett Foundation on her wishes, released an audio tape, in which she related the full story, believing that having done her duty in keeping his secret, that George deserved the recognition which was being denied him, closing the tape by saying: “Hundreds of people who have been saved by his money need to know that the man who they read about in dusty almanacs and miscellany books, helped them a great deal, and that his life, however blessed, was far from perfect, but he did the best with what he had, which was more than most, but still not enough.”